On Being Nice But Writing the Truth

By Anne Elizabeth Moore

As a young writer, it was always emotionally and psychically—although not biologically—appropriate when I was described as having balls. Chutzpah, too; Moxie and guts have also been bandied about. Fearlessness, certainly. I did not know any better. However, it takes a good deal of experience to achieve a state of courage. Courage demands an awareness of consequence, a willingness to try again what had previously proven difficult, painful, or impossible. Courage is a known commodity. It is desire, despite experience and fear.

As a young writer, it was always emotionally and psychically—although not biologically—appropriate when I was described as having balls. Chutzpah, too; Moxie and guts have also been bandied about. Fearlessness, certainly. I did not know any better. However, it takes a good deal of experience to achieve a state of courage. Courage demands an awareness of consequence, a willingness to try again what had previously proven difficult, painful, or impossible. Courage is a known commodity. It is desire, despite experience and fear.

A writer’s tools are limited. Pencil, or digi-pencil (in my case, a laptop named Anne Jr., III). Paper, or digi-paper. Language—any will do. Imagination. A writer’s potential for courageous acts therefore is extremely, frustratingly limited—or, seen from another angle, boundless. A variety of courage comes into play in novels about skydivers, non-rhyming poetry, or celebrity exposés. Upon inspection, however, we see that these all emulate courage, for the writer: they describe it, or suppose it, but do not necessarily take it. A writer can perform only one courageous act, ever, and most only accomplish it a handful of times.

Writers can write the truth. They do not always know how, and do not always choose to when they do know how. But it takes more than balls to do it.

To write the truth—as opposed to writing truthfully, writing down true things, writing one’s version of truth, or completing an assignment for the Think Piece Industrial Complex on the subject of truthiness—one must, according to Bertolt Brecht, accrue four skills beyond courage: the keenness to spot truth, the strength to wield it powerfully, the judgment to bestow it upon those who will use it, and the cunning to communicate it effectively.

Brecht wrote “Writing the Truth: Five Difficulties” in 1935, a pressing and relevant essay for the modern American writer. Look closely at what is implied: That truth is easily masked. That it must be situated properly. That it should be placed in the hands of those who require it most desperately. And that it must be transmitted fully, perhaps lovingly. The implications for Twitter alone are staggering.

Nestled within these difficulties is a particular (although not exclusive) challenge to the female of the species, relegated to a gender role rewarded for silence and prized when emotional. The final difficulty with writing the truth is the ability to withstand the constant admonishment—indeed, even wish—to be nice.

Female writers, according to VIDA’s byline tallies, rarely exceed 30% of those published in or reviewed by major US literary publications. Those of us who work in comics have it worse, rarely netting more than 10% of the opportunities at major comics publishers. On average, women earn 77% of what men do in the US. In comics, it’s 27%. In a culture that “RT”s, “friend”s, and “like”s perhaps more than it does “read”— definitely more than it does “pay”—being nice, or not, has real economic consequences. People who form sentences can now grow entire careers from a well-maintained social media account, many of which can’t be said to contain a speck of truth in the lot. For those of us who like people—as opposed to those who “like” them—this aggravates: I was nice before nice was the only way to get your book reviewed.

If you exclusively read me on the page, it may surprise you to hear that I like people, even love them. All of them. I want their lives to be easy and happy, even if I sort of disagree with them politically, when I want them to feel content but have no economic or decision-making power whatsoever. In which case I will gaily chat them up on the street but still write excoriating essays about their terrible ideas and how they must be stopped. It’s gotten me into trouble, sure. Hateful internet comments, lost funding opportunities, a machine gun once. Anti-me Facebook groups. Rape threats. I don’t date other writers.

To be nice, and a truth-teller, is not easy. You skip a lot of parties. People invite you still, maybe more often if you have publicly criticized them. But it is tiring to explain in person why you wrote what you wrote. “Because it is true,” is not something people understand these days. And not something any writer should have to explain, ever.

As a culture we value niceness, particularly in women, even at the expense of truth. And while I love you, dear readers—all of you—I can’t help but believe that that is bad. In fact, because I love you, I will continue to point out when you have erred, when you are supporting something damaging, and when you are flat-out wrong.

But we can still go out for ice cream after.

Anne Elizabeth Moore is a Fulbright scholar, the Truthout columnist behind Ladydrawers: Gender and Comics in the US, and the author of Cambodian Grrrl: Self-Publishing in Phnom Penh (Cantankerous Titles, 2011), Unmarketable: Brandalism, Copyfighting, Mocketing, and the Erosion of Integrity (The New Press, 2007, named a Best Book of the Year by Mother Jones) and Hey Kidz, Buy This Book (Soft Skull, 2004). Co-editor and publisher of the now-defunct Punk Planet, and founding editor of the Best American Comics series from Houghton Mifflin, Moore teaches in the Visual Critical Studies and Art History departments at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

She works with young women in Cambodia on independent media projects, and with people of all ages and genders on media and gender justice work in the US. Her journalism focuses on the international garment trade. Moore exhibits her work frequently as conceptual art, and has been the subject of two documentary films. She has lectured around the world on independent media, globalization, and women’s labor issues.

The multi-award-winning author has also written for N+1, Good, Snap Judgment, Bitch, the Progressive, The Onion, Feministing, The Stranger, In These Times, The Boston Phoenix, and Tin House. She has twice been noted in the Best American Non-Required Reading series. She has appeared on CNN, WNUR, WFMU, WBEZ, Voice of America, and others. Her work with young women in Southeast Asia has been featured in USA Today, Phnom Penh Post, Entertainment Weekly, Time Out Chicago, Make/Shift, Today’s Chicago Woman, Windy City Times, and Print Magazine, and on GritTV, Radio Australia, and NPR’s Worldview.

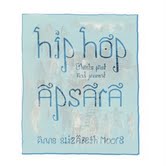

Moore recently mounted a solo exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago and participated in Artisterium, Georgia’s annual art invitational. Her upcoming book, Hip Hop Apsara: Ghosts Past and Present (Green Lantern Press, Aug. 28, 2012), is a lyrical essay in pictures and words exploring the people of Cambodia’s most rampant economic development in at least 1,200 years.

Website: AnneElizabethMoore.com