[alert variation=”alert-info”]Publisher: Thames & Hudson

Formats: Hardcover, eBook, Kindle

Purchase: Powell’s | Amazon | IndieBound | Barnes & Noble | iBooks[/alert]

“Over the past two centuries, peat cutters in the bogs of northern Europe have periodically unearthed the remains of prehistoric men, women and children so well preserved that they are often mistaken for victims of modern crime. In many cases their skin, hair, nails and marks of injury survive, betraying the violence that surrounded their deaths. Who were these unfortunate people, and why were they killed?” (Publisher’s blurb).

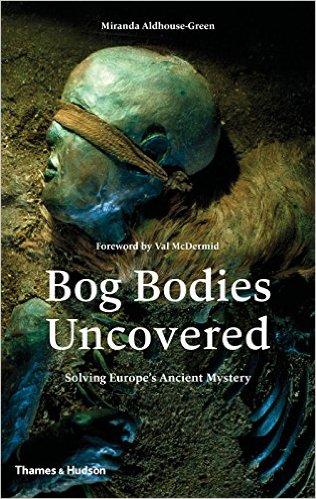

Who better to determine who these unfortunate people were and how and why they were buried in bogs than an anthropologist backed up by archaeology and an appreciation for crime scene forensics? The anthropologist is Miranda Aldhouse-Green of Cardiff University in Wales. She’s an expert on the European Iron Age, which lasted from the last few centuries BC into the first few centuries AD, and she has published several books on the ancient Celts and Druids of that period. Her book’s foreword is by Val McDermid, an award-winning crime novelist whose special passion is the art and science of crime scene investigation, and whose recent book Forensics: The Anatomy of Crime informs Aldhouse-Green’s study of the bog bodies.

Bog Bodies Uncovered is a modern sequel to The Bog People, a highly praised book published in 1969 by the Danish archaeologist Peter Vilhelm Glob. In The Bog People, Glob focused primarily on a few well-known bog bodies found in Denmark. By comparison, this new book provides details about the typically violent deaths behind twenty-five bodies found in the bogs of five countries: Ireland, England, The Netherlands, Denmark, and northern Germany. Thus, it is far more expansive and a welcome update on what has been learned and assumed in recent years about this unique, puzzling phenomenon.

With the exception of one found in Ireland and subsequently dated to 2000-1600 BC, the majority of the bog bodies are dated between the fourth century BC and the late third/early fourth century AD. Their discovery dates to the early 1800s, although most were found during the twentieth century, with the two most recent uncovered in 2003. Each body has been carefully studied and given a unique name for purposes of identification by researchers and for labeling in European museums where most of the remains are kept.

Here are three examples:

Haraldskaer Woman, a.k.a. Queen Gunhild, discovered in Denmark in 1835. Age: 45-50 years old. Died: c. 490 BC from “strangulation/hanging.” Condition: “Naked but with clothing near the body together with a long lock of hair; secured in the bog with hurdles.”

Yde Girl, discovered in The Netherlands in 1897. Age: around 16 years old. Died: c. first century AD from “strangulation with her woolen belt.” Condition: “Naked but covered by an old woolen coat; right side of head shaved… Suffered from severe idiopathic scoliosis that stunted her growth and would have caused her to walk with a lurching gait and to suffer constant pain.”

Osterby Man, discovered in northern Germany in 1948. Age: 55-60 years old. Died: c. 200 AD from “blunt force trauma to the head, decapitation.” Condition: “Skull with a fine head of hair, dressed in a complex Suebian Knot; wrapped in a deerskin; secured in the bog with stakes.”

The author, using modern crime scene forensic clues and historical cultural evidence – plus careful reading and interpretation of Roman-Empire-era writings (by Tacitus, Caesar, Vitruviuis, and others), and her own deep knowledge of European Iron Age life – proceeds in ten data-packed chapters to work out the probable (but uncertain) cause and date of each death, and to explain the condition of each body. Her chapters cover such research topics as “The World of the Bog People,” “The Magic of Bog Preservation,” “The Application of Forensic Science,” and so forth, and address such possibilities as accident, execution, murder, and human sacrifice.

What we know for certain is that most of the twenty-five bodies investigated were interred naked, though a few of them had articles of clothing laid nearby. Most were adults, but a few adolescents and children have also been found, including some with obvious physical, including congenital, deformities. Most were deliberately killed, though accidental drowning may have occurred in a few cases. Several of the bog bodies were dressed in fine attire, some with neatly manicured fingernails and a few with their hair fixed with gel, all clues to some sort of high or special social status. A few of the bog men wore their hair tied up rather elaborately in a Suebian Knot, which Tacitus describes (in his documentation of life in the far northern reaches of the old Roman Empire) as a hairstyle worn by warriors. (Google “Suebian Knot” to see pictures of this unique male hairstyle on a well-preserved bog body.)

The author of Bog Bodies Uncovered goes on to tell how they died. Most appear to have been murdered, showing clear evidence of violent deaths by hanging or garroting, stabbing, physical mutilation, decapitation, or bludgeoning. In crime forensic terminology, bludgeoning is called “blunt force trauma” and includes “catastrophic head injuries.” The author can only speculate, although quite knowledgeably with comparative examples, about why they died and were interred in bogs. Were some or all of them rogues and troublemakers? It’s hard to say, but the author does a grand job of giving us a variety of choices by examining such possibilities as witchcraft and magic or ritual violence. Some may have been slaves or prisoners of war (of either high or low rank). She also discusses the significance of marshes and bogs as “liminal territory,” describing how the bodies were deliberately interred there “between land and water, between the living and the dead.” She goes on to explain that “bogs were surely regarded as terra inculta, wild, ungovernable territory belonging to no one and beyond the bounds of order and control, places rarely visited and perhaps always feared”; in short, “fitting places for the inexcusable dead.”

These are just a few hints at the depth and breadth of this remarkable book. While the author follows a largely forensic anthropology approach to the bog body mysteries, it is written in an easy-to-read style without obtuse technical jargon or theoretical posturing. The book has eighty-two illustrations, an introduction, an appendix, notes, a bibliography, and an index.

Recommended read for enthusiasts of ancient history and culture, or of inexplicably macabre human behavior.

[signoff predefined=”Social Media Reminder” icon=”twitter”][/signoff]