[alert variation=”alert-info”]Publisher: Washington State University Press

Formats: Paperback

Purchase: Amazon [/alert]

Who knew that Walla Walla was famous for something far more serious than their delicious, sweet onions?

Unusual Punishment: The Penitentiary in Walla Walla – 1970 to 1985 by Christopher Murray should be required reading for students in criminal justice educational programs who want to work within the corrections system when they graduate. Like the Stanford Prison Experiment, Unusual Punishment is a rare glimpse into the psychology of both inmates and correctional officers. Except, Unusual Punishment does not document a study of volunteers pretending to be inmates and guards but a real-life prison. Policy makers can learn from these chaotic years of the Washington State Penitentiary that prisons are fragile ecosystems. Any change in how a prison operates may have unintended and sometimes fatal consequences.

In addition to people interested in criminal justice and psychology, this is also an interesting look into the sociological history of prisons. In the past, prisons were extremely boring. As Murray writes, “As the 1960s came to an end, the Washington State Penitentiary was an ordered and predictable world.” Strict regulations made the day-to-day life of an inmate monotonous. However, something changed so that prisons could become the backdrop of riveting drama as fictionalized in TV series such as Oz, Prison Break, and Orange is the New Black. Part of that change is explained in Unusual Punishment.

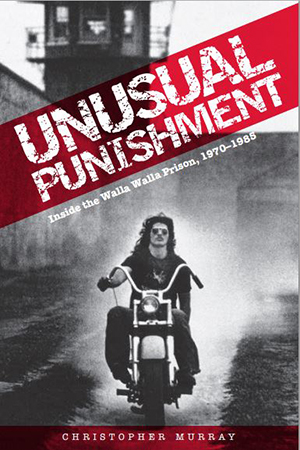

In the 1960s, government officials began to talk about reforming convicts. Instead of merely housing criminals, they hoped that correctional education programs would rehabilitate inmates into becoming law-abiding citizens once their time was served. In addition to better serving prisoners, the Department of Social and Health Services (DHSH) also made it more difficult for wardens to easily hire or fire personnel. In November of 1970, four reforms shifted power between guards and prisoners. By December, the prisoners went on strike for the freedom to wear their hair long, grow beards, and don their own clothes. By January, there was a murder. Within four months, two more inmates were killed. There had only been three murders in the last 10 years, but within four months that number had doubled. Where there had once been honesty among thieves, now beatings and robberies took on racial tones. Heroin arrived. There were more beatings and killings. Rape became rampant. A motorcycle gang enacted a new sort of order within the prison walls. Guards, fearing for their lives, had a high turnover. The ones who stayed stopped doing their job, began drinking too much, or became ruthless with an us-versus-them attitude.

As the old convict code eroded, the strong dominated the weak and the wannabes reinforced the culture. The price of survival was sometimes a shattered soul.

Unusual Punishment is broken down into the various stages of this reform period: super custody, changes, descent, nadir, war, and transformation. The 50 concise, dense chapters would be excellent for classroom discussions. Also, there are photos and site maps of the prison during these years. Murray conducted over four-dozen interviews with inmates, correctional officers, and government officials in order to write this incredible piece of journalism. While this book is not the definitive book on how prisons should be run, Murray’s byline sums it up well as “an extraordinary chapter in American prison history.”

[signoff predefined=”Sponsored Review Program” icon=”book”][/signoff]