[alert variation=”alert-info”]Publisher: Inkwater Press

Formats: Hardcover, Paperback, Kindle

Purchase: Amazon | IndieBound | Barnes & Noble[/alert]

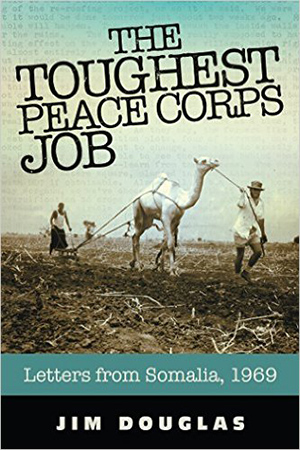

While campaigning for president, then Senator John F. Kennedy addressed 5,000 students at the University of Michigan, challenging them to contribute two years of their lives to help people in countries of the developing world. Within weeks of his inauguration, on March 1, 1961, President Kennedy signed Executive Order 10924, which established the Peace Corps on a temporary pilot basis. Since then, more than 220,000 Americans have served the Peace Corps in over 140 countries.

It was a tremendous leap of faith for Kennedy to send young Americans into the developing world. Would they come running home? Would they create international incidents? What kinds of kids would even volunteer to do this? Host countries would want to know if these Americans would bring the knowledge and skills they needed in the modern world or would they constitute a corps of neocolonialists marching through their country?

The 1960s was a time when few Americans, who were not soldiers, had ever been outside of the U.S., nor did many know much about other countries or other cultures. At the time of his deployment to Somalia in November of 1968, Jim Douglas was but a recent college graduate wishing to educate Somalis on agricultural development. He thought he was ready, but he was psychologically and emotionally ill prepared to deal with the experience that awaited him.

Jim Douglas joins a long list of authors who have compiled letter anthologies recounting their respective Peace Corps deployment experiences, many from the 1960s or 1970s. Perhaps what separates Douglas’ experience in Somalia is the challenging nature of his assignment. Many other areas, of what had commonly been referred to as the “Third World”, certainly presented their challenges: cultural as well as physical and emotional. What was particularly challenging for young, middle-class Americans headed to Somalia, however, was the fact that the Somali language was purely verbal, not written. Moreover, different dialects were spoken in different regions, making even Somali-speakers unintelligible to others. On a higher level, Somali society is ontologically anathema to Western conceptions of society (and vice-versa), defined as it is as clan-based, pastoral, and often nomadic, never having conformed to the modern Western nation-state system forcefully imposed upon them.

Douglas acknowledges that his relative immaturity led to sarcasm in his letters and journal entries that was a source of embarrassment to him (note in particular his letter dated March 18, 1969 and his journal entry dated April 5, 1969). Indeed, had any one of his many letters and journal entries been discovered by the Somali authorities, the scandal would have dwarfed that which occurred in 1961 when a postcard, written by a volunteer describing her first impressions of Nigeria’s living conditions, was found by a local student. Not realizing her comparisons would be an affront to her local community, and that the anonymous nature of the U.S. postal process would not apply in another country, this short communication home made front page news in Nigeria (and beyond) and very nearly shut down the Peace Corps program.

While at times duplicative, the tone of Douglas’ letters and journal entries makes for an interesting story and epitomizes the risks not only inherent in Kennedy’s plan, but in remaining unenlightened and shortsighted about other philosophies, cultures, and world views, and how conflict is generated and addressed in places with such different views. How would the manifestations of the psychological toll taken on volunteers – a toll vividly displayed throughout Douglas’ recounting – be conveyed back home, especially to policymakers? The negative answer has unfortunately been displayed time and time again, including in Somalia itself, when the U.S. failed spectacularly during its intervention in Somalia in 1993 with the notoriously vague and shortsighted goal of establishing a secure environment for humanitarian relief operations as soon as possible.

While beyond Douglas’ immediate scope, it was his hope – and goal – that others like him could recognize the need to transcend whatever initial cognitive and psychological dissonance they experience when engaging with other cultures as a path toward successful mutual communication. It will take far more than reviewing a recounting of experiences to get us anywhere near such a path, but it cannot hurt.

[signoff predefined=”Sponsored Review Program” icon=”book”][/signoff]