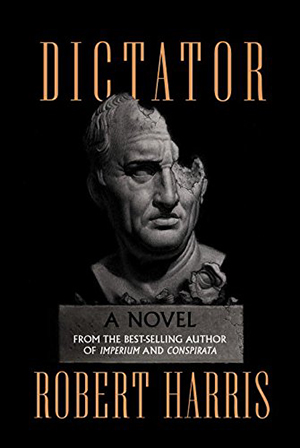

[alert variation=”alert-info”]Publisher: Knopf

Formats: Hardcover, Paperback, eBook, Kindle, Audible

Purchase: Powell’s | Amazon | IndieBound | iBooks[/alert]

Cicero (106 to 43 BCE) was one of the last civilian leaders of the Roman Republic. Born into a well-off but obscure country family in the provincial town of Arpinum, he managed to become one of Rome’s leading lawyers and orators in a time of increasing violence and civil war. In a time where leading politicians raised private (or privatized) armies, Cicero managed to stand up for the republican government and the rule of law without the support of his own army or a massive fortune. He was perhaps Rome’s last civil leader who rose to power without the support of an army or gang.

Dictator tells the story of Cicero’s final years, ranging from his exile to Greece in 58 BCE to his death in 43 BCE (the year after Julius Caesar was assassinated). Cicero increasing finds himself becoming irrelevant in a polity dominated by warlords such as Pompey the Great, Julius Caesar, Marcus Antonius (Mark Anthony), and ultimately Augustus Caesar (then known as Octavian). This personal tragedy is intermixed with the tragedy of the collapse of the Republic, under the weight of the ambition of its leading men and the internal contradictions of city-state republic ruling over a large and diverse empire.

The novel is the third installment in Robert Harris’ Marcus Tullius Cicero trilogy (preceded by Imperium and Conspirita). This series of novels is a fictional account of Cicero’s life written by his famous aide and secretary, Tiro, who was Cicero’s indispensable assistant throughout Cicero’s storied career. Tiro actually did write such a biography, but it was lost to the ages during the tumult and turmoil that occurred when the Roman Empire fell. In this admirable series Harris seeks to recreate this work based on historical sources, and this series adheres very closely to the historical record. Truly, the reader can only conclude that if we had Tiro’s actual work it would be very similar to this well-written series of novels.

Harris also pays a good deal of attention to Cicero’s famous and less known writings undertaken during his forced retirement. Cicero really wanted to be a philosopher more than a politician and lawyer. The plot device of having Cicero’s learned slave secretary Tiro recount the story really pays off here because the two discuss the details of Cicero’s compositions and what he was trying to accomplish. As Harris speaks through Tiro, these retirement writings: “complete[d] his great scheme of absorbing Greek philosophy into Latin and of turning it in the process from a set of abstractions into principles of living.” By no means is this literary history, but rather a nice side addition to the story which enriches of our understanding of Cicero. The death scene of Cicero is very well done, and allowed him to apply some Stoic philosophy.

Different authors and historians have variously characterized Cicero’s role during this time as ineffective, self-centered, vain, or (as in this novel) as an idealist seeking to preserve the Roman Republic. Harris’ Cicero is an industrious and tough-minded man, harsh in judgment of stupidity, and dedicated to the preservation of the Republic.

Cicero equates liberty with the republic. Anyone reading this book might imagine that Roman senators were democratically elected, but the franchise was greatly restricted, and the Senate was a self-perpetuating oligarchy. In the centuriate assembly which elected high officials, including the consuls, even free males if they were poor were effectively disenfranchised.

For about a hundred years before the timeframe of this book, those who attempted to carry out reasonable reforms – the Gracchi brothers, Marcus Livius Drusus – were killed by fellow senators. The senatorial faction that Cicero would one day lead used violence before the reformers, or “populists” as Harris calls them, ever did. Thousands of democrats were executed without trial and thrown in the Tiber at one point. When Cicero as consul advocated and carried out the execution without due process of five Roman citizens for sedition, he was following an old pattern. The people unsurprisingly lost trust in the republic, that is, in the rule of the Senate; they favored Caesar, a “populist.” These facts are not emphasized in this book.

While this book is the third in the series, one can read this work without the others. Any dependence to the earlier works is introduced with adequate background such that one should not be left questioning what happened. For factual accounts of Cicero’s life one can refer to Elizabeth Rawson’s Cicero: A Portrait or to Anthony Everitt’s Cicero: The Life and Times of Rome’s Greatest Politician, both of which are relatively short, yet provide a cogent history of Cicero and the context of the time in Rome.

[signoff predefined=”Social Media Reminder” icon=”twitter”][/signoff]