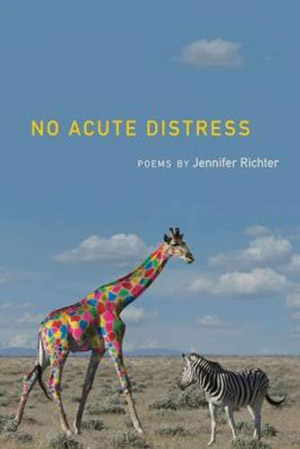

[alert variation=”alert-info”]Publisher: Southern Illinois University Press

Formats: Paperback, eBook, Kindle

Purchase: Powell’s | Amazon | IndieBound | iBooks[/alert]

“Did you hear the one about the woman whose illness made her confuse happiness and sadness?”- Pleasant, healthy-appearing adult white female in no acute distress

The poet Anne Sexton once said, “Put your ear down close to your soul and listen hard.” In Jennifer Richter’s poetry collection No Acute Distress, Richter has her ear pressed directly to her soul’s acute form of rhythmic yet detached language. What she hears back and puts into poetry is a therapeutic lesson in motherhood, loss, medications, indifferent doctors, aging and witnessing one’s own mortality through one’s own children.

Richter’s style sits mainly in a prose phase. She ventures out into different modes with poems like “Demeter Has Never Liked Family Game Night,” and “I Find Myself Shelved Between Rich and Rilke,” but her style seems pressed for the prose format which like Anne Sexton puts the patient to doctor relationship on full display. Sexton wrote many of her poems to her doctors, such as “You Doctor Martin,” “The Operation,” “Her Kind,” and “Doctors” – that’s good company to be in for Richter as she works in a similar vein. The parallels range – Sexton has much more going on stylistically, her poems are deeper and darker (not many poets can touch her here), and in poetry her intangible power was something that struck in places few poets could emulate. Richter does well in her own ways – seeing how she witnesses her children through poems like “Mom, watch” and “My Daughter Brings Home Bones,” which bring things home with her. There’s a detached nature here that never tells us too much but rather allows us to experience her poetry, and that’s what she shares most with Sexton – and that’s why she’s worth reading.

Her opening poem, “Pleasant, healthy-appearing white female in no acute distress,” is a prose piece starting with the opening line “Fancy seeing you here!” coming straight from her surgeon. As the nurses look on, her surgeon continues to quip in italicized phrases with things like “Hi Smiley,” and “Come here often?” Richter is going under anesthesia which creates a surreal and nice short poem. The phrases may not be literal and the replies back are soft but in one quick line turn insightful: “Did you hear the one about the girl whose illness made her confuse happiness and sadness?” Then Richter fully detaches and refers to herself outside of her body in the final few lines as “her,” saying “she grinned’ when referring to herself.

The poem is a nice balance between a prose poem and a more straightforward poetic structure. It tells us a story, but also has the poetic sense to not reveal too much – Richter always adds a nice bit of mystery to her work. We’re never directly told who she is, or who her children are. In fact we’re never directly told much of anything too specific, yet we experience her poetry enough to have it make an impression and in that, we have the most poetic sense there is gifted to us: the intangible, and feeling evoked simply through words. As she finishes “Pleasant, healthy-appearing white female in no acute distress,” the words from the doctor in italicized phrases become a subconscious form of poetic ambiance. The poem ends with the doctor asking Richter how she is, “Never better,” Richter wails, “Never better.”

The poem that follows the opener, “Mom, watch,” is another prose piece and one of the better ones in the collection. From a distance Richter watches her son, Luke, and another boy playing in the yard as the piece opens, “Pink drifts line the street where my son crouches, scoops, and comes up flowering.”

“Flowering” here is an interesting word choice. Normally it would seem off, adding a bit of a vague and abstract term to an action her son is taking while scooping up leaves. The flowering is more about coming into age for both Richter and her son, but the image is also of her son shooting up with the colors in the air and his body the stem. The line works here, Richter gets away with it despite it being a bit of an out of place line. The direction Richter takes, however, is “vertical.” As the two boys climb trees, her son falls, “A mother’s life is horizontal,” she writes.

Indeed. In a short span, Richter is pacing in a waiting room, folding her son’s jacket and waiting to see him. As the poem continues, her son won’t stay sick in bed, “I wanted him to stay that way, but our natures aren’t the same.”

It is in contrast to her nature that Luke is soon up climbing trees again. Richter now always watches the tree her son climbs, noticing the jays and the mother on the branch who shuffles back and forth horizontally – seeing which one of her babies will jump and fall or which will which fly. It’s a helpless feeling and Richter illustrates the position well – being a mother who wants to intervene but also let her child grow on his own.

Richter does expand from the prose poem form. In “Diptych: Ho Chi Minh City” she sets up two sister poems side by side, the first called “Reproduction” it is one of the best poems in the collection. Here Richter removes anything literal and creates a surreal landscape of melted clocks and starry dusks along the curbs of Bui Vien Street. She gives us just enough imagery and, through the title of the poem, enough to understand her meaning as she finishes with the following stanza:

“And now inside me vibrates Van Gogh’s Sky

Its glowing yolks and rush of swirling sperm

Above a town of tiny people we can’t see.”

This poem is followed by “Once A Mother,” where we can see the result of “Reproduction” and why they may be considered sister poems. “Once A Mother” is the result of “Reproduction” – here a toddler fusses over his mother’s lap in a Saigon restaurant. We’re gifted with exceptional language and another poem while once again going in the right direction still manages to stray from anything too literal. Richter is painting with her words here as she describes her surroundings:

“Painting; young boy, red tie, roughed cheeks;

Incense, gladiolus, jackfruit, rice bananas”

Five sections create No Acute Distress. Some are brief, such as “Examination,” which does something interesting: in the second poem of the section, “Eighteen Seconds,” the poem breaks into 10 short prose poems that all work nicely off of one of another; it’s the best insight provided into her psyche. Poems like “My Daughter Brings Home Bones” are also highlights, where Richter’s daughter, Chloe, has brought in bones from the backyard and laid them out on the driveway during Richter’s 40th birthday. Femur, rib, jawbone with a few flat teeth attached, dozens of thin arced parts – the bones are arranged along the street – the beauty is in the mortality and life witnessed at the same time as Richter watches her daughter, understands how she was born and will live long after Richter herself is gone.

The prose poetry aside – Richter also has poems that work in different favors. She plays with form in poems like “Demeter family game night,” and “Relapse,” although to less effect. Her strength lies in her language, and when she never strays too far from simple experiences that she is able to find the beauty in her relationship to her body, and specifically to her doctor, are evocative of Anne Sexton. Sexton was more lyrical and delved far less into the prose form, she was more manic – often breaking into unreachable states – it allowed for poetry outside of herself, she was able to write simply what her soul felt. Poems by Richter such as “Disappearance” and “Still Life,” are in that realm. Her conversations with her doctor are never straightforward and much of her later sections write like therapy sessions, including “Admission”, “Examination,” “Complications” and finally “Release.” But Richter’s life seems to be in and out of doctor’s offices, for her children’s birth and for her own condition. The condition seems like indifference from doctors or at least like they’ve seen it all before. From Richter it is delirium, crying fits of happiness and breakdowns of communication.

Consider poems like “Today’s lack of response suggests that the patient is not a significant placebo responder” where the desensitized language, and outward approach to her own condition, as if coming from an overworked doctor. The best thing about Richter is that she does not tone down her work; she sticks to the truth of her words, whether it’s her relation to her children, her own mental conditions, or her desires and pleasures such as in poems like “After You’re Sliced In Two.” No Acute Distress makes for a short collection. It can be read in a sitting, although it does tend to lessen its impact towards the end. Richter, whose acute distress may find harmony in poetry, has turned in a strong collection – her pieces are well wrought, molded and conditioned pieces of existence. They haven’t all come easy for Richter, but in a short span they give us the experience of romance, illness and motherhood as she has felt and lived them. Like Richter states in her concluding poem “No Joke,” “Even the quality of light is new, I’ve come so far.” Indeed she has, and thankfully for us created an exceptional collection of poetry.

[signoff predefined=”Social Media Reminder” icon=”twitter”][/signoff]