What is it here I have done

And am waiting for?

For what it’s worth, love,

A stone asks the same

Question of the river

Have I broken you yet?

– Bone River (I.)

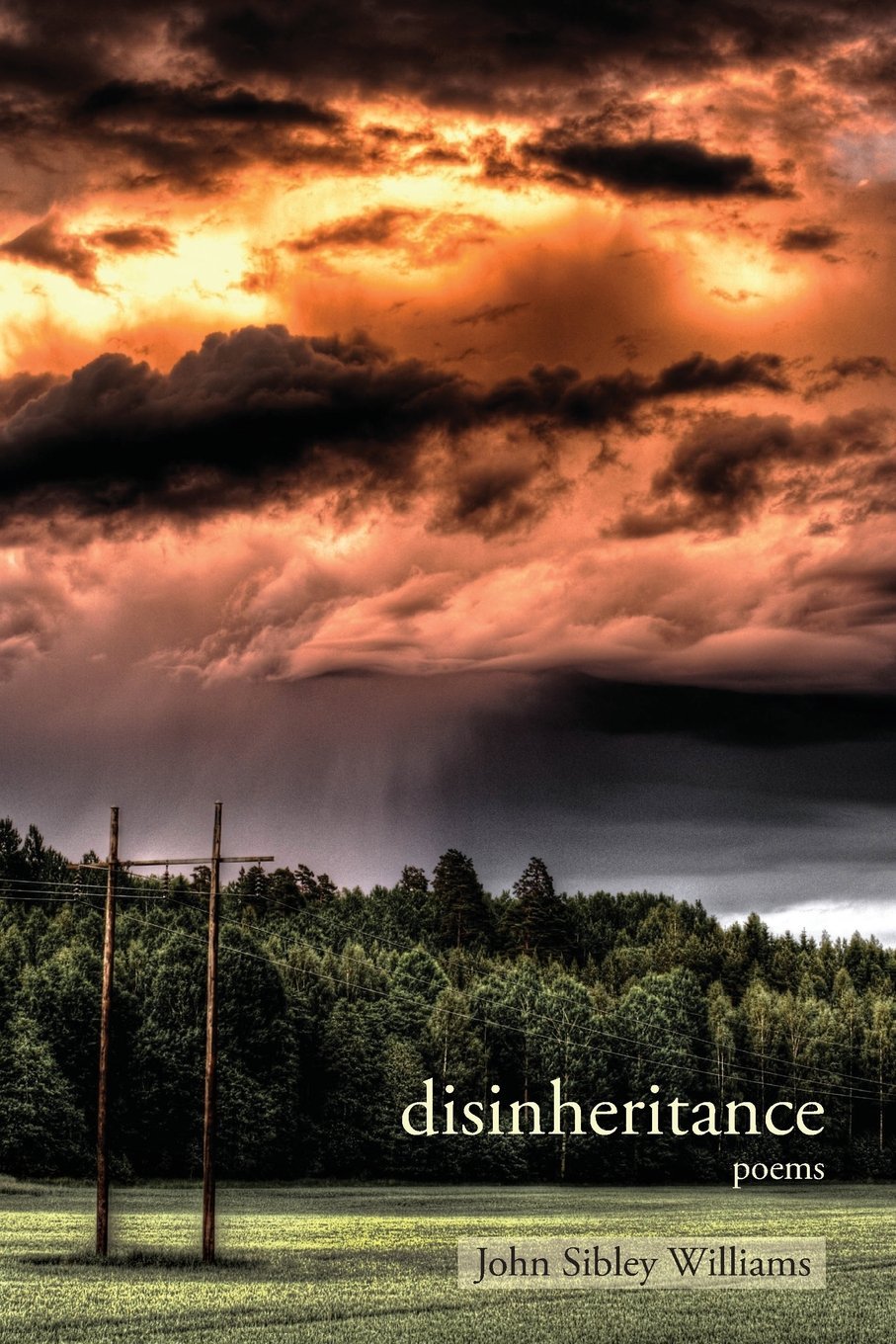

This question arises at the end of the poem in John Sibley Williams’ Disinheritance. It’s a retort meant for both the reader and for an unknown subject. Where such a figurative “breaking” may take place in Williams’ collection of poems is up to interpretation but it seems to be more a question with no real answer – one that is explored but never quite found.

[alert variation=”alert-info”]Publisher: Apprentice House

Formats: Paperback, eBook, Kindle

Purchase: Powell’s | Amazon | IndieBound | iBooks[/alert]

There are actually four poems in Disinheritance with the same title, numbered I-IV: “Bone River.” Bone River (I.), the first poem in the series, starts with a workable vague image of a child moving their parents’ limbs and is described as a raw and enigmatic gesture. This, like many of Sibley’s poems, doesn’t exactly provide us with any clear answers, nor really any clear depiction of meaning. But it is an acceptable opening poem, where Williams linguistically gives us some nice phrases but the larger question rises – is the echo of these poems a redundancy? Is there meaning in the repetition?

The prevalent theme of grief can be found in many of the titles, such as “Grief Is A Primitive Art,” “A Dead Boy Speaks to His Parents”, “A Dead Boy Fishes With his Dead Grandfather”; the message is clear, and a little overdone. But for how plainly written these titles are they do approach some emotional depth. Williams has heart, and many of his poems that reflect on grief and loss are moving but not particularly notable in breaking any difficult or routine poetic contrivances. Consider some final stanzas of “Grief Is A Primitive Art” and the lines below:

Arbitrarily I’ve decided

To depict the sheets,

As a cancer,

Your body a shadow,

Our tears an empty vase,

And faith

Has forever been rendered

A shallow cup

Inches from our lips

It’s rather inside the box poetry. The sheets are compared to cancer, your body compared to a shadow, tears compared to an empty vase – the comparisons become a muddy and uninspired stanza. It’s difficult to both find the unique concrete details in poetry, and to portray them as the art of words in a unique fashion is more of the difficulty of the art. But much of this is found in a revision, in a second, third, fourth draft which digs just a bit deeper. I think Williams can get there but symbolically what’s written is not groundbreaking poetry.

I do like his language in poems like “Truce,”which although falls into many similar issues has the excellent line:

The moon’s face drifts across the river

And I miss the hard geometries of coffins.

It’s a hard-hitting final line and It works here due to the image evoked. If you consider for a moment poets like Anne Sexton who in her poem “For Eleanor Boylan Talking With God” writes “Now my chair is as hard as a scarecrow.” The comparison of a chair to a scarecrow is not so much in the literal but in what they both symbolize.

Chairs and scarecrows aren’t necessarily similar but the idea of each of them – based on universal qualities one would associate with them – allows readers to feel the chair and gives of the haunting imagery and feeling behind the poem. This works as well to a larger extent the texture of both which in a literal sense could be described. In Sexton’s comparison, it is a break of the figurative into both an intangible and collective feeling that also works in contrast to a child-like wonderment of god.

That is some of the difficulty of good poetry. WIlliams’ comes close to stronger poetry on a few occasions. I’d liken him to poets like Joseph Somoza and even WS Merwin. Poems like “A Dead Boy Speaks To His Parents” play with form a bit in their break-downs but they possess many of the same flaws. There variance between themes is thin and never goes beyond what we already learn from the first sections of Disinheritance – that death is a part of life and sometimes what one’s entire life consists of. These poems are not about moving on, but rather being perpetually in a state of grief.

His best work lies in poems like “November Country,” “Truce,” and “Frontiers.” All of which don’t seem to try too hard and get the imagery right. There is a deep feeling of loss in Williams no doubt. His poetry reflects that. I was moved on more than one occasion, but again in the words of Anne Sexton, the most practical advice one can hear as a poet, “press your ear down to your soul and listen hard.” A few more drafts of some deep listens and I think Williams’ poetry will be stronger for it.

[signoff predefined=”Social Media Reminder” icon=”facebook”][/signoff]