An old Cherokee teaches his grandson the story of the two wolves that are at war inside of him and everyone else. The good wolf is a medley of positive emotions whereas the bad wolf is a combination of the negative. When the child asks his grandfather which wolf will win, the old man laughs and says, “The one you feed.”

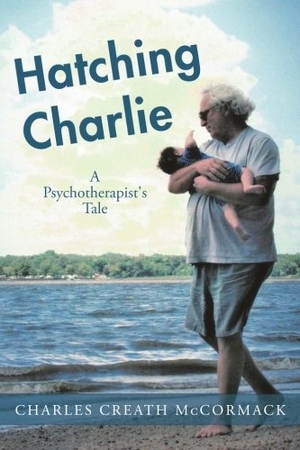

[alert variation=”alert-info”]Publisher: Hatching Charlie

Formats: Paperback, eBook, Kindle

Purchase: Powell’s | Amazon | IndieBound | iBooks[/alert]

Charles Creath McCormack recounts this well-known fable within the early pages of his autobiography Hatching Charlie: A Psychotherapist and references it throughout. Not only does the moral guide his life, but it also pays tribute to the time-honored tradition of an elder bestowing the wisdom gained during his lifetime upon younger generations. This is essentially the goal of Hatching Charlie:

“I’m writing [this book] for all of you: my children, nieces, nephews, and their children and, as importantly, for any strangers, yet my brothers and sisters in humanity, that happen upon this text and recognize it for what it is—a story of the follies and wisdoms of the human condition or at least one man’s version of it” (xi).

McCormack explains that the pursuit of happiness requires striving to embrace all thoughts, both good and bad.

The term “hatching” is used metaphorically as McCormack’s rebirth throughout the different stages of his life.

The narrative is mostly chronological as McCormack describes the complexities of his childhood. He describes his father’s teachings as “tyrannical and sadistic, interspersed with manic moments of humor and gut-splitting laughter, fueled by all the tensions and anxieties that had preceded it” (3). His relationship was much better with his mother, a pious woman, but his childhood still resulted in insecurity, mistrust, shame, and doubt. A fear of loneliness and isolation was borne when he was left at a boarding school in Strasbourg, France against his will:

“The psyche is like a tree trunk, early experience forever imprinted on the tender flash of the inner rings. And just like the tree, the inner rings become the foundation upon which all else rests” (1).

As with most children with abusive backgrounds, his young adulthood was a mishmash – in some ways he was too mature for his age and in others less. He tells about odd jobs, college, wanderlust, and then beginning the path of his life’s work, psychotherapy.

The stories of his patients, while sometimes shocking, are not gratuitous. Examples of a few of the most influential patients illustrate how psychotherapy shaped McCormack, not vice versa:

“Over the years, I’ve learned the importance of acknowledging my own less than socially acceptable thoughts and feelings. Consequently, this has helped me to better relate better not only to my patients but to all people. My patients feel recognized, understood, and accepted because they are. They know because they can feel it. I look over to them, not up or down at them, as fellow travelers in this obstacle course called life. A course that leaves none of us unscathed. Indeed, I see many of my patients as possessing extraordinary integrity and courage in their willingness to examine their lives. This will to vulnerability stands in stark contrast to that of others who are not even aware or interested in examining themselves; who dismiss the very notion of problems or weaknesses of any kind, much preferring their polished story-lines over any honest examination of themselves or their relationships” (177).

In essence, this describes Hatching Charlie, a testament to McCormack’s willingness to examine his own life and publish it so that others might benefit.

McCormack doubles back and briefly talks about his roles as a husband, father, and grandfather. These provided additional lessons that formed him, but these are more of an afterthought.

McCormack previously authored the 1989 article “The Borderline/Schizoid Marriage: The Holding Environment as an Essential Treatment Construct” and the 2000 book Treating Borderline States in Marriage: Dealing with Oppositionalism, Ruthless Agression, and Severe Resistance. However, he admits that writing does not come naturally to him. Indeed, the style and tone of Hatching Charlie would not be mistaken for an overtly stylized MFA memoir, but some might find this a benefit rather than a detraction. McCormack comes across as sincere, the likable everyman who has traversed through life’s peaks and valleys. He dedicated at least two years to this autobiography, which has paid off in the writing’s polished presentation. There are many quotable passages that resonate because of the reflection he’s done on his own life:

“The key? Learning to look at ourselves honestly and get out of our own way in the practice of following our hearts rather than our fears” (389).

Socrates famously said that the unexamined life is not worth living. By reading about how others, such as McCormack, have examined their lives, perhaps this task is made a little easier for the rest of us.

[signoff predefined=”Sponsored Review Program” icon=”book”][/signoff]