[alert variation=”alert-info”]Publisher: Wheatmark

Formats: Kindle, Paperback

Purchase: Powell’s | Amazon | IndieBound | Barnes & Noble | iBooks[/alert]

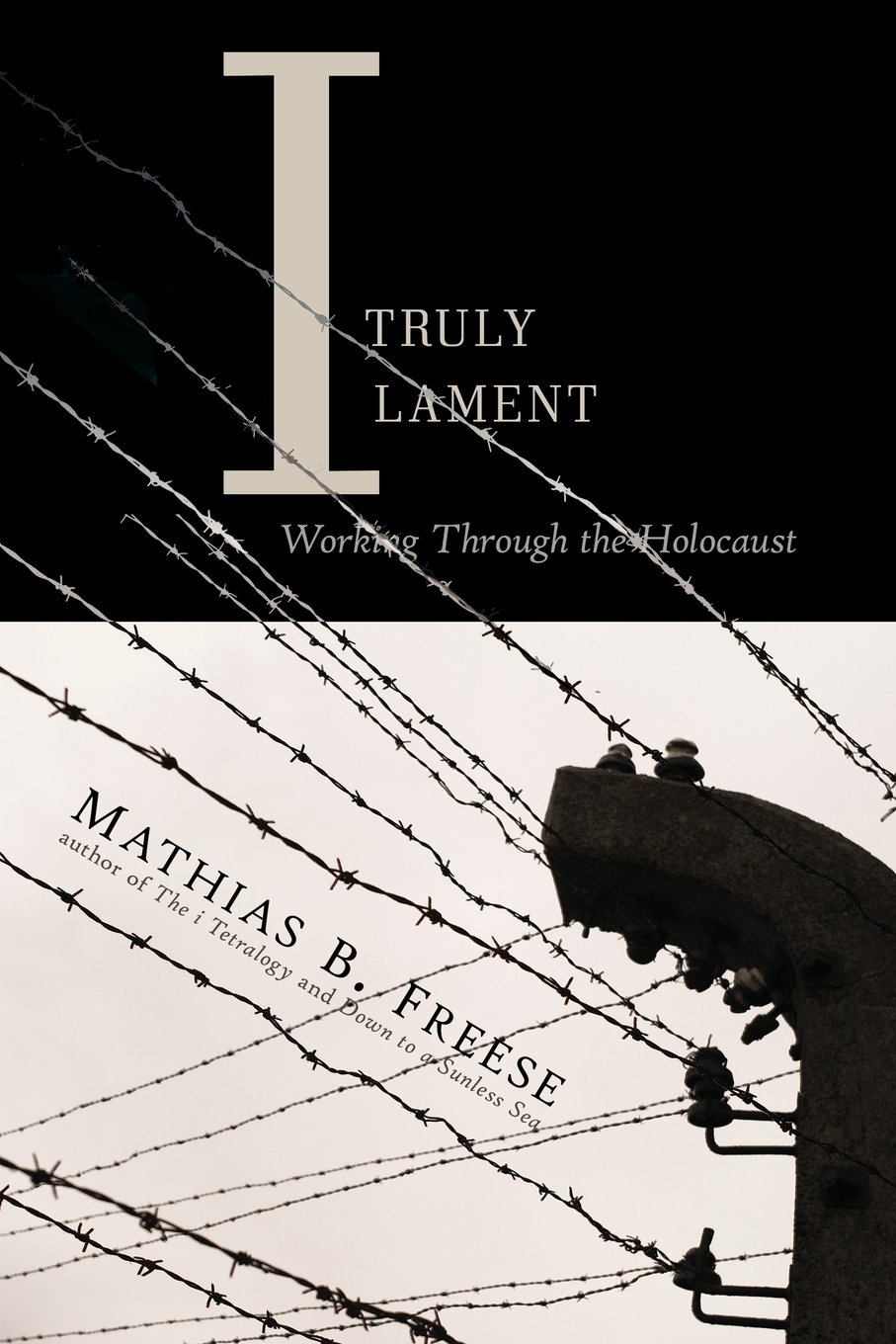

Writers struggling to understand the Holocaust have published hundreds, if not thousands, of books. Novels and memoirs search for meaning, recall the horrific suffering, find gems of compassion hidden beneath the oppressive German regime, or attempt to comprehend how a mass of individual humans can be capable of inflicting such cruelty onto other humans again and again. Others, such as Mathias B. Freese’s new short story collection I Truly Lament: Working Through the Holocaust, plunge the reader into the psyche of the pursued, the imprisoned, and the survivor.

I Truly Lament: Working Through the Holocaust is Freese’s fourth book, following some acclaimed works. In addition to being a writer, Freese is also a teacher and psychotherapist. Even without reading the author’s bio printed on the back cover, the reader soon grasps that he or she is in the hands of a highly educated writer. Each of the 27 short stories is introduced by a quotation from one of Freese’s previous works. They are poignant punches to the solar plexus. Introducing a short story on a prisoner debating suicide is the following quote: “And now I am entering the last of my repertoire – dread, the last sweat of existence, the husky, porcine breath of imminent, terrifying death.”

The quotations are well chosen to reflect the stories that follow, but the stories are filled with similar sentiments. Each sentence taken morsel-by-morsel is equally vivid, imaginative, and well written; however, packed together the overall effect becomes heavy handed and Freese’s attempt to make the horrors into striking images certain to penetrate the reader’s callused heart results in the opposite effect. In the story the above quote introduces, the narrator contemplates throwing himself against the electric fence: “Given the gruesome task I intend to accomplish, snow provides grace and access, for it blinds the guards and gives me opportunity for my task. Snow blankets heavily like a profound idea upon the mind. In has substance, character, things I admire but lack.”

The description is beautiful, morbid, and picturesque. However, words like “gruesome” reveal the melodrama. Instead of feeling the prisoner’s desperation, the narrative skims the surface of his stream of consciousness. Granted, suicide is a particularly difficult subject for any author to capture, but this story was chosen at random during the writing of this review. A similar example could be extracted from any of the 27 stories.

“To hold a child’s hand is to hold tomorrow.”

Interestingly enough, in the short metafiction piece contained in this collection, Freese imagines a letter from Max Weber, a Holocaust revisionist, in response to Freese’s request to review his novel that makes a similar critique. Weber’s imagined response is that Freese’s writing is clever, but hyperbolic. “You plunge into the psyches of these individuals with a heavy hand, and although I found this striking at times, I often rejected it as so much literary slush, grabbing the reader with effects. Sex is always fireworks.”

Freese does indeed use sex to grab attention. In several short stories, he makes passing comments to Hitler’s sex life and one is devoted entirely to a fictional interview with his lover, Eva Braun, who reveals the kinky side of the dictator. However, the collection is not all fireworks. One is in the style of an essay on the much-coveted personal paraphernalia of famous Nazis. A few delve into magical realism by including golems, unreliable supernatural beings. Several describe the depravation of the concentration camps. The survivors of these camps, who invariably settle in Arizona, consider themselves too damaged to have spouses, really live their lives, or do anything much more than idle away the rest of their years. With a few exceptions, these aren’t stories so much as imagined glimpses into characters’ inner monologues. Nothing is left for the reader to glean, lest the reader misinterpret.

While it’s understandable that Freese wants to be clear and dynamic, especially since he is actively refuting those who believe that the number – six million – of Jews exterminated in the camps is grossly exaggerated and that it’s a myth that Nazis turned Jewish fat into soap. Such horrors are difficult to fathom for believers and non-believers alike. The human mind can comprehend things on a personal level, if there’s a distinct face or voice to relate to, but statistics remain too abstract. It’s necessary to zoom in on one individual at a time. This has been a painstaking process for Holocaust writers, and has been well executed by a number, including Anne Frank, Markus Zusak, Elie Wiesel, and Viktor Frankl. Each of these authors hones in on one perspective and allows the horrors to unfold in everyday language. In contrast, Freese makes the same mistake as hundreds of other World War II fiction writers by surrendering to the temptation to attempt to shock the reader without the proper build up. For a reader, the sudden thrust of a pile of corpses, suicide, or anal sex will never be able to bring to life what an unforgettable personality will. With an unforgettable personality, the reader will cheer at the character’s triumphs and weep at the character’s sorrows, and both are necessary for vision of this character to become a complete person as lifelike as the readers’ family. Unfortunately, most of Freese’s short stories only show partially developed characters.

Ultimately, this book is for those who cannot read enough about the Holocaust and are willing to savor this book bite by bite rather than digest it as an entire meal.

[signoff predefined=”Social Media Reminder” icon=”facebook”][/signoff]