Saving Stonehenge: A History of the Preservation Movement in England

Saving Stonehenge: A History of the Preservation Movement in England

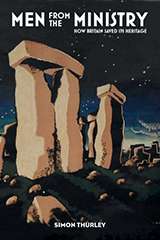

By Simon Thurley

Yale University Press, $45.00, 224 pages

One of the most unexpected themes running through Men from the Ministry, Simon Thurley’s engaging account of the preservation movement in Britain, is just how modern that movement is.

When it was established in 1815, the Office of Works served as the first governmental organization with responsibility for historic sites. In England, these included a rich tapestry of medieval patrimony: cathedrals and abbeys dotted the countryside, while, closer to London, castles and palaces fueled a growing public appetite for the “olden times”. Home to Henry VIII, Hampton Court, for instance, attracted more than 350,000 visitors in 1851. Other sites, too, garnered considerable public interest: the Tower of London, like Shakespeare’s home in Stratford, welcomed record numbers of visitors throughout the later nineteenth century.

“The bones of our heritage are the tangible and visible remains of our ancestors, their achievements, their industry and their ideas of beauty.”

As Thurley makes clear, it was the responsibility of the Office of Works (and the men of its Ancient Monuments Department) to develop a strategy both for cataloging and administering sites worthy of preservation. Doing so required that it first establish a definition for “heritage”, which was synonymous throughout the Victorian era with “the impress of national character”. In 1913, as the First World War approached, the Office recast the term according to a more expansive set of criteria: sites were to be evaluated not only according to their reputation and history, but their architectural, archaeological, and artistic merits. Slowly, the English landscape was transformed: what started in the nineteenth century as a disparate network of monuments had been converted by the twentieth into a chorus of interconnected sites, each contributing to a larger national narrative.

Ultimately, the Office of Works (and its successor, English Heritage) achieved what it set out to do: associate English identity with what Thurley calls the “physicality” of England. No longer was Stonehenge a remote cluster of rocks; like so many other sites preserved over the past 200 years, it served instead as the basis for a story about the triumph of a nation and its people.

Reviewed by Jesse Freedman

[amazon text=Buy On Amazon&asin=0300195729][amazon text=Buy On Amazon&template=carousel&asin=0300195729]