[alert variation=”alert-info”]Publisher: NYRB Classics

Formats: Paperback, eBook, Kindle

Purchase: Powell’s | Amazon | IndieBound | Barnes & Noble | iBooks[/alert]

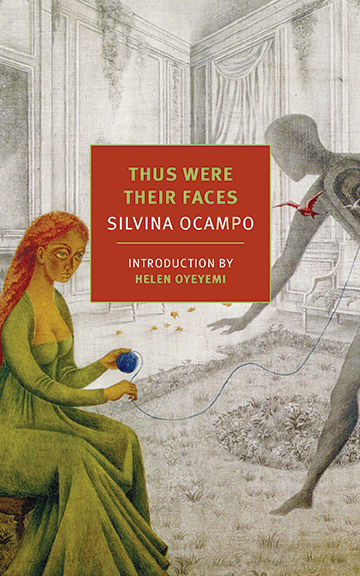

New York Review Books has done it again, granting new life to yet another neglected gem of world literature. I had never heard of Silvina Ocampo before picking up this title, but when I saw that NYRB was putting out a collection, and that authors like Borges and Calvino much admired her, I knew there was a hole in my literary knowledge that must be filled. I was not disappointed. Ocampo’s Thus Were Their Faces is a collection of short stories boasting enough merit to put her firmly in ranks with the masters of the form – like Borges, O’Connor, Poe, and the like. In my mind, she is the Argentinian Shirley Jackson, with every story evoking a fantastic atmosphere – at once creepy and inviting. Ocampo is a literary angler, drawing her piscine audience closer to the hook with every mysterious sentence until we bite at the bait and she reels us in. Her characters are broken, rubbing against the realm of the civilized world with disturbing results. The fantastic world she creates is not a world of happy truths and pretty vistas, but one of reverential longing and obsessive destruction. I absolutely adore it!

Many of Ocapo’s tales toy with the innocence of childhood (or the lack thereof). At the cusp of adulthood, her characters’ romantic innocence brushes against the strict mores of adult society with perilous results. These child-like subjects cannot cope with the civilized order of the modern world and, as a result, become the agents of chaos and destruction. In the titular tale, a group of children from a school for the deaf are visited by an angel, we are told, and become unified in the appearance of their faces and the notions of their minds, much to the wonder and concern of their caretakers. In the end, they are all said to have died in a tragic plane crash, but all witnesses report that they were taken by the angels. It is as if the children represent the spiritual ideal of the world, in which there is a great togetherness and the reasons for strife are all lifted from them. But these children cannot fit into the real world, and thus are dramatically whisked away by their angelic protectors.

In “The Mortal Sin,” a young girl about to take her first communion is forced by one of the servants to watch as he commits some unspoken (probably sexual) act upon himself. The child values her purity and piety above all, choosing to live ascetically (the resulting irony being that her parents reward her with great luxuries), but she cannot bring herself to confess to what she has seen. Consequently, she is plagued for the rest of her life with the knowledge that she has taken communion in a state of deadly sin. The tale is told in the second person, so we can only imagine that it is Chango, the abusive servant, the only other person who knows her secret, who is telling this tale with a sick, almost pious, joy in his voice. This little girl, who wants only to be good and pure, can find nothing but corruption in the world and must suffer throughout her life – ignorant of the state of her soul.

The story, “Voice on the Telephone,” tells of an affluent boy, Fernando, who, during the middle of his birthday party, hides in the couch and becomes a voyeur to the intimacies of the female adults nearby, stealing fancy matches in the process. Unattended by the parents or servants, he and the other children set a fire in the room with the parents, locking them in and burning them alive. But Fernando is more concerned with an expensive Chinese chest of drawers having survived the fire. His apathy for the lives of the adults is cloaked with childlike innocence, his actions and attitudes only a mirror reflecting these uncaring adults.

Another great thematic element of Ocampo’s work appears to be a great fascination with memory, especially in terms of how it determines reality and identity. For this reader, “The House Made of Sugar” is perhaps the most memorable tale told and deals with memory in precisely these terms. It tells of a superstitious young woman, Cristina, who moves into a house, which looks as if it was made of sugar, just after she is married. Her husband has lied to Cristina, telling her that they are the first people to live in that house, for he fears that she would not want to live there otherwise. He goes to great lengths to shield Cristina from the truth, gathering the mail before Cristina and trying to head off meetings with neighbors. All the while Cristina becomes more reserved, her usual happy demeanor turning to one of sadness. She loses all her superstitions and gains the ability to sing. She begins to feel as if she has the successes and failures of another person. The reader is left to wonder if it is the actions of the husband that has provoked such change in Cristina, but what has happened is something much more fantastic. Strangers begin to mistake Cristina for Violeta, a previous tenant of the house made of sugar, with vivid memories of her, so much so that Cristina actually begins to believe it—packages for Violeta come to Cristina, past lovers adamantly believe Cristina to be Violeta, warning her to stop seeing other lovers. Cristina’s husband searches out the true Violeta, finding only an old voice coach of hers, who informs him that Violeta is dead, tormented by the belief that someone had stolen her life. In the end, Cristina leaves her husband, becoming Violeta wholly. Cristina became Violeta in the memory of others, and as such, became Violeta in reality. The real Violeta lost those memories, and in that suffered a death of identity. It is a truly haunting tale that seems to warn the reader what a slender thread our lives hang on, that these ephemeral memories are the only ties to our beloved identities and lives.

In “The Autobiography of Irene,” Irene treats the knowledge of her future as a form of memory and thus inactively and serenely awaits the hour of her imminent and unavoidable death, passing the time by reluctantly telling her life to her biographer. In “The Objects,” the exact objects of Camila’s childhood begin to reappear in her life. She grows so concerned with the nostalgia of these objects that she cannot cease caressing them and “finally enter[s] hell.”

It is memory that defines the terms of life for Ocampo, and when reading her classic stories as they are presented by NYRB in Thus Were Their Faces, we are certain to breathe a new life into them with our remembrance. I, for one, will never forget that uncomfortable feeling of reading these fascinating tales for the first time. This reviewer highly recommends this volume for the lover of fantastic short fiction or world literature in general. Within is a strange world all its own, with memorable characters and elegant prose. It is worthy of becoming a popular classic and not just a forgotten footnote in Argentinian literature.

[signoff predefined=”Social Media Reminder” icon=”twitter”][/signoff]