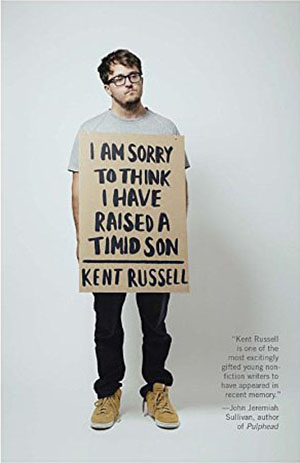

[alert variation=”alert-info”]Publisher: Knopf

Formats: Hardcover, Paperback, Kindle, eBook, Audible, Audio Book

Purchase: Powell’s | Amazon | IndieBound | Barnes & Noble | iBooks[/alert]

Collections of essays have always made for popular nonfiction reads, and it’s often interesting to see how the author(s) tie their essays together – either with an encompassing theme or lack thereof. I Am Sorry To Think I Have Raised A Timid Son by Kent Russell contains eight essays with a strong focus on interviews he conducted with either groups of people or single persons, all of whom don’t necessarily fit into society. The title of the book, taken from a quote by Daniel Boone, announces the presence of his own father in all of the essays as well. The interviews, for the most part, are insightful and fresh. It’s not everyday an average guy finds himself among people who prefer old fashioned ideals or enjoy painting their faces with clown makeup daily. Russell’s interviews take him all over the world, leaving his audience with a fascinating read, to say the least.

I Am Sorry To Think I Have Raised A Timid Son doesn’t seem to know what it wants to be. Although presented as a collection of fascinating essays about all these differing people, each essay is combined with stories about Russell’s own father. This would make much more sense if the experiences shared had some connection to each of the essays they appear in, but the stories never seem to bear such semblance. It feels almost as if the author wants to take a break and just share a random tidbit about his dad before delving back into the meat of the essay. Needless to say, it makes very little sense, and is frustrating because the main topic of each essay is always much more interesting than the diversion. On that, it should be noted how the stories and interviews with Russell’s father are the most uninteresting part of the entire book. Like every male nonfiction writer, Russell wants to write on all these moments between him and his father, building them up as philosophical and important, but they never come off that way. They’re just brief glimpses of his personal life that don’t add to the overall picture. All seven of the first interviews lead up to the final chapter, which is, of course, an interview with Russell’s father that took place over the course of a one-day road trip. After so many interesting conversations, this final installation might leave the reader a bit discontented.

That does, however, lead into the book’s stronger quality: all of the (other) interviews. Russell hunts down people either withdrawn from society or for whom society has withdrawn itself from. He first meets with a childhood friend returned from fighting overseas, followed by (what has to be the most fascinating chapter in the entire book) his time spent at the Gathering of the Juggalos. The following chapters look into ex-hockey players, a man who’s become immune to venom by letting snakes bite him every day, and Tom Savini, the man behind such Hollywood gore as Dawn of the Dead and Friday the 13th. With these first five interviews, there seems to be a trend of violence, as the author heavily focuses on the gore of these people’s careers and life choices. However, the following three interviews are that of the Amish, a man living on a secluded island, and his own father – violence not tying into these stories at all. It seems that Russell has an interest in the solitary; those who don’t expect the world to understand them or grasp why it is they do what they do – except, again, for his own father. All of these interviews are wonderful, but rounding them up with Russell’s father makes little to no sense.

The author does put some heavy focus on the history of hockey and baseball, as well as the story of Daniel Boone, which slows the essays down considerably, but as a whole the book makes for an interesting read. However, the biggest issue with the text is the sheer lack of women present. Russell’s own mother is only mentioned in passing, as are his sisters, and no other woman is brought to the forefront of his stories. Some females are written about in the Juggalo and Amish chapters, but they take a backseat to all the men Russell chooses to interview over them. The book seems to boil with the heavy undertone of “what makes these men men?” The author can’t be faulted too much, as he is only relaying personal experiences, but it does beg to question why he didn’t go out of his way to find an female to interview who had similar experiences to any of these men.

Despite the lack of a female presence and some slow paced chapters, the entire book is made of solid writing. The author has quite a way with words, and writes in almost a prose-like manner at times. Although some parts of the book do drag, I Am Sorry To Think I Have Raised A Timid Son makes for a truly fascinating read for the unique lifestyles Russell has the opportunity to encounter. That, alone, might make the reader forgive the author for all the hang-ups on his father.

[signoff predefined=”Social Media Reminder” icon=”twitter”][/signoff]