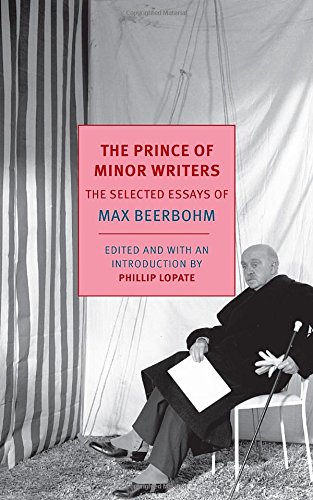

[alert variation=”alert-info”]Publisher: NYRB Classics

Formats: Paperback, Kindle, eBook

Purchase: Powell’s | Amazon | Barnes & Noble | iBooks[/alert]

I typically look forward to a collection of essays with a dread akin to that of a dentist appointment. It is not that there is anything necessarily bad with essays or dentists, I just find them both boring and uncomfortable. The essayist tends to address subjects about which I have no care and in a manner that I find most bland. Luckily, there are exceptions – NYRB’s new Max Beerbohm collection, The Prince of Minor Writers, is one of them. While the apparent subjects of his essays would seem quite dull at first (for example, knighthood, servants, or the differences between hosts and guests), Beerbohm never ceases to entertain with the eloquence of his prose and his dry humor. In a trite, yet appropriate, phrase, he is a master of his craft. His words are beautiful and his thoughts are oftentimes quite profound and universal, relevant not just to late nineteenth/early twentieth century Britain, but to all times.

Beerbohm writes as a man apart. He preferred intimate company rather than the company of crowds, but as a theater critic he was often deep within the crowd and spent a great deal of time there. He was a man caught between two worlds – the stagnant social structure of Britain in his youth, along with its youthful, romantic outlook; and the cold, hard, modern world where the class system began to disappear. It was a period of great change in Britain, and Max Beerbohm was a chronicler of an art and a life caught in the midst of this revolution. Beerbohm seemed unafraid to love and hate both this new world and his old world. In one breath he lampoons the democratized institution of knighthood and in another laments the loss of a beautiful valley to railways and other signs of modernity. Because of his unbiased nature, his judgments read as sincere and worthy of consideration, when in other cases we might think the writer to be a grumpy, old atavist denying the ways of his new, unfamiliar world.

At one point, Beerbohm boasts his fortune that he is an essayist, for, in being so, he is not bound by the need to research or prove anything, but remains free to opine and entertain – and entertain he does. He is not a serious art critic or social commentator, but rather a silly one. At one point he writes a humorous paean to “Kolniyatsch” – a fake novelist he creates to show the vogue of the Russians among the literary elite of his time and the formulaic praise often given to those writers – scathing commentary on both writers and reviewers. Perhaps the most entertaining essay in this collection is an account of firefighters, that “Infamous Brigade,” who become villains because they thwart a great enjoyment in the art of fires. Saving people from burning buildings creates an anti-climax – the scene would have been much more dramatic if the people had burned alive! As such, he advocates the creation of an Artists’ Corp to harass the fire brigade, to serve the public as protectors of the fine art of public fires. While very humorous, it doubles as a commentary on the new ideals of the modern world (and its art!) turning society on its head.

Beerbohm never approaches any subject straightforward, but always meanders his way to the heart of his essay, guiding you there, allowing you to follow instead of leading you there. There is no formula. His writing always feels fresh and its essence true. An essay by Beerbohm is like watching a dance grow more and more elaborate, leaving you to wonder what the devil it is all about. Then, all of a sudden, it shifts and we perceive the precise point about art or English society that he has been making all along. That careful manipulation of his audience is his genius. He is in actuality discussing people under the veil of critiquing their works. To Beerbohm, art and people are not divorced, but insoluble. To write of one is to write about the other, and Beerbohm understood this truth.

Yet always with Beerbohm is the reverence for those works of art (and, I think he would say, people) that are hidden from him – for Beerbohm holds an insatiable imagination. It seems he became bored with the trite and obvious in his later years. Indeed, he writes at one point about how he would like to establish a museum that exclusively houses only unfinished works of art – the place of honor belonging to a lost portrait of Goethe by Tischbein. His imagination waxes about this piece and others, noting with open wonder its myriad possibilities. But Beerbohm freely admits that the actual piece, if found, would likely fall short of the expectations of his mind. Art lives not on the stage or on the walls, but in Beerbohm’s mind, where all good art twists and mingles. He is a romantic, concerned with the passionate human relation to the art – so much so that there is no greater art than the hidden work that can be completed only in the mind. To further illustrate this point, in another essay Beerbohm speaks of a statue of Umberto that stands covered while it remains in perpetual legal dispute. But Beerbohm does not wish it uncovered. Rather, what is more wonderful to him is what he imagines the sculpture to be, with all the knowledge of the dispute that it has caused. I imagine art for Beerbohm is the art that is made in his own head, not the words that people print or the pictures that they paint. The wonder of the world resides in the human mind, and not on the external.

In his essay, “The Crime,” Beerbohm is so put off by a book that he impassionedly throws it into the fire. At first he takes comfort in it, sorry only that he harmed a book, but then he sees the words on the page as they are incinerated and he becomes consumed with the imaginings of what he has missed, so that, in the end, he is paying for his crime with his doubts. Did he miss a novel perfectly sublime? It is an extremely poignant piece that very much compares to our experience as readers when there are so many choices regarding what to read; it is easy to grow perplexed and full of doubt. For every book read there is another that is neglected and the titanic “what if?” looms into the mind to block all our triumph. We readers carry with us the burden of a Sisyphean task – the literary collection of the world is too vast for one to read it all; there will be gems we shall miss – and we are consumed with sorrow. But don’t let this NYRB collection of Beerbohm’s essays be one of those “what ifs?” that haunt you. Don’t read this review and look at the words in the fire and let the book burn. Rescue it, read it, and treasure it.

[signoff predefined=”Social Media Reminder” icon=”facebook”][/signoff]