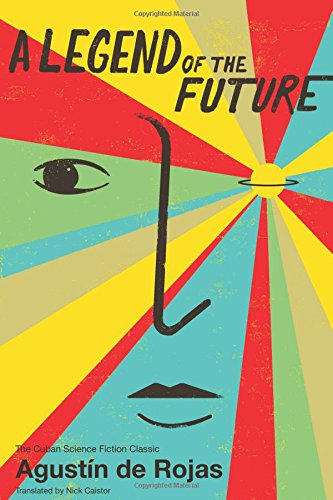

[alert variation=”alert-info”]Publisher: Restless Books

Formats: Paperback, eBook, Kindle

Purchase: Powell’s | Amazon | IndieBound | Barnes & Noble | iBooks[/alert]

At last, they are finally publishing science fiction from Cuba, starting with A Legend of the Future by Agustin de Rojas. Hailed as the father of Cuban science fiction, this work was first published back in 1985 and is only now being translated into English and published thirty years later. Let me assure you, it is a pity that it took so long!

The story starts in typical sci-fi fashion. On a return mission from Titan, testing a new form of interplanetary drive, the ship, Sviatagor, hits a small meteorite and is critically damaged, killing three members of the crew and leaving the other three mortally wounded. Still, these brave explorers concoct a plan to complete their mission and return their ship to Earth, regardless. The two functional crew members, Gema and Thondup, having been irradiated to a deadly degree, the clock of their lives slowly ticking away to silence, attempt to replace the damaged computer of the ship with the brain of the third member, Isanusi, who was left paralyzed in the accident, so he could pilot it back to Earth after they both expire from radiation sickness.

What really sells this story is not the situation (which is terribly reminiscent of 2001 and Tau Zero), but the psychological focus on the characters. The Sviatagor team was assembled at an early age by the compatibility of psychological profiles necessary for long space voyages. But they have grown dependent on their relations with the others, and, as a result, the loss of so many crewmembers is a terrifying blow, especially to Gema. Thondup activates her conditioning (think something akin to brainwashing or hypnotism to make her less emotional) in order to ensure her stability as they struggle to complete the mission. There is an obstacle to their plan, however: Isanusi’s knowledge of the imminent loss of his fellow shipmates jeopardizes the return to Earth (because of their interdependency he is unable to function as a solitary unit), and consequentially Gema and Thondup attempt an emotional meld with Isanusi so that they live on more presently in his disembodied mind.

In the background of this action is the current political state of the Earth. The Earth is divided into two factions: the Federation and the Empire. The Federation appears to be a more benign, communist-like government concerned with the exploration of space and the advancement of humanity throughout the galaxy (don’t forget, this was written in Communist Cuba over thirty years ago!). The Empire appears to be about to crumble in the excesses of individualism, brought low by a vacuum in leadership caused by the invention of “dream palaces,” in which brains are brought to live in incessant pleasure, separated from and never returning to the harsh realities of the world. These dream palaces threaten the very nature of humanity, especially among the “neanderthal” people, who make up a great number of the population as their only goal is pleasure and not the advancement of man (and thus they are susceptible to the false allure of these dream palaces). This terrestrial situation becomes poignant as Isanusi’s brain becomes the ship’s computer in a manner akin to the dream palaces, the major difference being that Isanusi is not divorced from the external world, but rather interacts with it and contributes to it while having to suffer the memory of a more corporeal life with his close friends all now deceased.

The novel constantly juxtaposes the self and the group, pondering whether the group is able to overcome the limitations of the individual self. Rojas seems infinitely curious about group psychology, emphasizing the constant need to evaluate and to adapt to the situation. He perhaps even explores the strong meld between the crewmembers, thought to be essential for long-term space travel (and coexistence on Earth?), as some symbol of the communist ideal. Isanusi’s sacrifice of his corporeal self for the sake of the mission helps to justify this reading.

While the questions Rojas ponders are thought provoking, the prose lacks a certain beauty (perhaps as a result of translation). The story is primarily told as a string of dialogue, both internal and external, with no differentiation between the two, causing mild confusion to the reader. But perhaps Rojas intended this stylistic approach to express the individual dialogue becoming the group dialogue in his idealistic, communist future. If so, kudos to him; I found it a little tedious and distracting. Also tiring, Rojas describes few actions except those simple statements that express one character acting upon another—all other action is told in dialogue. There is also no sense of place other than what comes out during the dialogue, which often feels forced in order to give even this meager sense of locale. As a result, it reads more like a play.

Still, as the book progresses and the story becomes more of what transpires in Gema’s head, these idiosyncrasies bothered me less and I came to admire Rojas’ lesson conducted with the crew of the Sviatagor: namely, how the limits of individual humanity can only be surpassed through cooperation and dependency upon our fellow man—sometimes at great personal sacrifice. If A Legend of the Future is idealistic science fiction, colored by the politics of its age, then it is idealistic science fiction at its best—concerned with the fate of mankind among the stars and not with spaceships and gadgets and alien races. I remain curious as to what else Cuban science fiction has in store for its new, English-speaking audience. For those of you who are also curious, start with A Legend of the Future.

[signoff predefined=”Social Media Reminder” icon=”twitter”][/signoff]