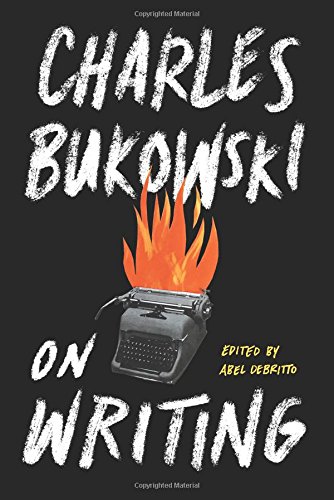

[alert variation=”alert-info”]Publisher: Ecco

Formats: Hardcover, eBook, Kindle

Purchase: Powell’s | Amazon | IndieBound | Barnes & Noble | iBooks[/alert]

“What matters most is how well you walk through the fire.”

Henry Charles Bukowski, Jr (‘Hank’ to friends and family) was a noted German-born American poet, novelist, and short story writer of the mid- to late 20th century. Bukowski (b.1926) was an inexhaustible writer, personally troubled but publically acclaimed. His thousands of poems were widely published in magazines and collections. Many of his hundreds of short stories are found in the collections Hot Water Music and South of No North: Stories of the Buried Life (‘No North’ is not a typo). His six novels were entitled Women, Post Office, Ham on Rye, Factotum, Hollywood , and his last, Pulp. He also wrote innumerable notes and letters to friends and strangers, especially to other writers, and to publishers and editors.

In preparing Charles Bukowski on Writing, the editor, Abel Debritto, estimates that he pored through some two thousand pages of unpublished correspondence, seeking the writer’s most insightful observations on writing. In them, Bukowski shares his insights on the dreariness and drudgery of being a writer, on the art of creation, and on life in general, his own unsteady life in particular. Bukowski illustrated much of his hand-written correspondence with doodles and sketches, most notably those from his infamous decade of drunk (1945-1954).

These personal letters and notes, fractured and rambling, are mostly about the angst and the art of being creative. The best way to understand them, in this provocative book, is to read them (aloud) and chew on the words, while enjoying his imaginative (often drink-inspired) sketches, which he signed ‘Buk.’

In 1965, he wrote to Henry Miller, the more famous but equally unconventional American writer, “well, it’s my 45th birthday, and on that poor excuse I take the leniency of writing you—although I damn well imagine you get enough letters now to drive you screwy.” Two rambling paragraphs later he admits he’s “drunk, a little, as usual, yes,” and again, “where am I? another beer? of course.” In between those admissions he rattles along about reading a book by the French novelist Louis-Ferdinand Céline. He writes that someone “gave me copy of Celine’s – what’s it called? – Journey to the End of the Night. now listen, most writers make me sick. their words don’t even touch the paper. thousands of millions of writers and their words, their words don’t even touch the paper. but Celine. made me ashamed of the poor writer I am, I felt like tossing it all. a god damned master whispering into my head. god, I was like a little boy again. listening. there’s nothing between Celine and Dostoyevsky unless it is Henry Miller.”

Another example of his off-hand style, brilliant but full of anguish, comes in the ‘Introduction’ to his 1970 book Dronken Mirakels; Andere Offers, from Cold Turkey Press (published in Dutch, but never in English): “Looking over these poems – to put it simply and perhaps melodramatically: they were written with my blood. They were written out of fear and bravado and madness and not knowing what else to do. They were written as the walls stood, holding out the enemy. They were written as the walls fell and they came through and got hold of me and let me know of the sacred atrocity of my breathing. There is no out; there is no way of winning my particular war. Each step I take is a step through hell.”

Regardless, he is considered one of the most influential recent American writers. He lived in Los Angeles and what he wrote there, how he felt, his view of the world and life, reflected the moods of the city and his own disordered existence, especially his struggles with alcoholism, women, and writing.

Somebody once asked him, “What do you do? How do you write, create?” He replied, “You don’t… You don’t try. That’s very important: not to try, either for Cadillacs, creation or immortality. You wait, and if nothing happens, you wait some more…”

The epitaph on his tombstone reads ‘Don’t try.’

This collection of letters is an enlightening, if challenging, read, so go ahead: Try it! With a beer.