[alert variation=”alert-info”]Publisher: Gallic Books

Formats: Paperback, eBook, Kindle

Purchase: Powell’s | Amazon | IndieBound | Barnes & Noble[/alert]

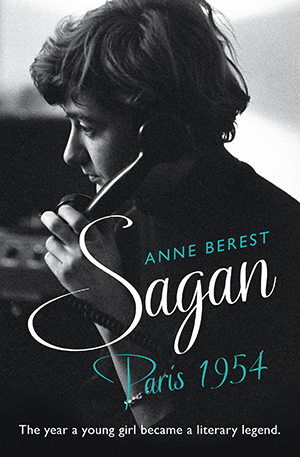

In 2014, Anne Berest, a popular contemporary French writer (and actress) was asked by Denis Westhoff, the son of Françoise Sagan, to write a book to revive the memory of his mother, one the iconic French novelists of the twentieth century. In 1954, the (then) eighteen year old Françoise Quoirez (pen name ‘Sagan’), a teenage rebel, wrote her first book, the controversial and best-selling Bonjour Tristesse. The novel – Hello Sadness in its English translation – is a girl’s coming-of-age story, sometimes compared with J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye (1951). Very soon after publication, Bonjour Tristesse won the prestigious Prix des Critiques book award, which catapulted Sagan to instant fame and acclaim. Over the rest of her life, Sagan wrote plays, two biographies (one was of Brigitte Bardot), several autobiographical studies, and nineteen more works of fiction, all well received though none of them gained the high level of praise that her first and most youthful novel had earned.

Anne Berest, who was born twenty-five years after Sagan’s Bonjour Tristesse was published, doesn’t tell us if she had actually met the famous novelist, but she was certainly familiar with Sagan’s writings and fame. In Sagan, Paris 1954, Berest takes pains to tell us that it is “neither a biography, nor a journal, nor a novel”; but is simply “a story. … the story of a girl, a very young girl, writing her first novel. … the story of the few months leading up to the publication of Bonjour Tristesse.”

Sagan, Paris 1954 is a kind of literary nonfiction (a form of creative nonfiction), describing events and conversations that, if not absolutely correct, ring emotionally true and faithful to what is known (in this case) about Sagan at a particular time in her life. Someone has called it a ‘fictional memoir’, though ‘literary memoir’ is, perhaps, a better term. Whatever we call it, Berest’s book is the sort of story that is difficult to write and, for parts of it, challenging to read. Yet, Berest succeeds if not brilliantly, then certainly with a cool style and aplomb. Her success is due, in part, to inserting herself into the narrative, drawing upon her own life to highlight Sagan’s accomplishments.

After completing the memoir, Berest told Sagan’s son that writing his mother’s story was like a gift with an embedded ‘secret plot’ within it that emerged as “an unlikely friendship between a lady of a certain age, now dead, and a young woman born two generations after her.”

“During all those weeks of work,” Berest writes, “we spoke to each other almost every day and our conversations, which I derived from her books and from her life, were interrupted by nothing and by no one. Like my other friends, she pointed me in the direction of books that I would not otherwise have read, she helped me understand a thousand things that were obscure to me, she propelled me towards people I would perhaps not have considered, she richly filled hours that I would otherwise have let slip by. … Françoise Sagan has surrounded me with her benevolence, has influenced my actions and thus, in accordance with the butterfly effect, has determined my whole life, the life I have ahead of me—for I believe that to be the role of friends, great friends.”

This may all seem a bit weighty, but if you read the memoir, and Sagan’s original novel, you will undoubtedly feel the impact of their stories. It’s an absorbing read, and if a creative memoir is supposed to be memorable, this one succeeds.

Throughout Sagan, Paris 1954, we are struck by the fluidity of Berest’s thoughts, the breadth of her insight, and the depth of her quest to describe those few months in Sagan’s life. At one point, for example, Berest describes the discovery and rush to publish Bonjour Tristesse. She also relates how, early in her own career, Berest was employed as a reader at a Paris publishing house where she spoke up for a first novel by yet another young woman who went on to become a noted writer.

“Some years later, at a dimly lit Parisian party,” she recalls, “I ran across that same girl, who was now famous on account of her book. … Needless to say, we were still both the same age as each other. But the success of her book had catapulted her into what seemed to me to be life as it was meant to be lived, whereas I was vegetating in the limbo of my own mere existence. I asked her for a light, and she obliged, but in an offhand way, without even bothering to look at me.”

“I often think of that incident,” she goes on, and “I wonder which of the people who cross my path, their faces unknown to me, have nonetheless played a part in my life without my being the slightest bit aware of it.”

This attention to two individuals reconnecting after a span of time comes across as if Berest is reminiscing how her own life might have intersected with Sagan’s, though Berest was not yet born when Sagan’s talent was discovered. It’s almost as if they had mystically met in 1954, then reconnected, like the girl at the “dimly let Parisian party,” sixty years later during the writing about Sagan’s life in Paris.

Sagan, Paris 1954 is a unique and inspiring book, recommended for readers attracted to French novels and novelists, literary memoir, and for anyone who may simply want to see a good example of superlative writing.

[signoff predefined=”Social Media Reminder” icon=”facebook”][/signoff]