[alert variation=”alert-info”]Publisher: Inkwater Press

Formats: Hardcover, Paperback, eBook, Kindle

Purchase: Powell’s | Amazon | IndieBound | iBooks[/alert]

More books have been written about the Vietnam War than about any other American war. The “official” version of the war lost credibility early and individuals had to make sense of it for themselves. A large number wrote books based on their experiences, many of which were published by small presses or by the authors themselves and received no distribution to speak of.

There is a sizable body of very good literature about a war, which, by most accounts, was a very bad war. It is as if the books have to be exceptional, in order to have a chance of measuring up to the task of outweighing or counterbalancing the war. Of the nobler examples of the human behavior, the Vietnam War of popular imagination provides little evidence. The country was so polarized about Vietnam that by the mid-Sixties putting any kind of positive spin on the war was seen as a reactionary political statement, no more credible than the daily military press briefings which came to be known as the Five O’clock Follies.

It has taken a generation for the war to lose enough immediacy that it can be looked at with something of a cool eye, and discussed without raised voices – most of the time. Vietnam rent America apart as no war had since the Civil War, and the wounds are still tender. The literature of this war has the double task of revealing those wounds in the first place, as well as providing the vision and understanding to try to heal them.

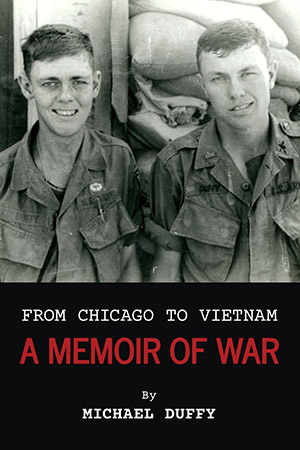

In his book, From Chicago to Vietnam: A Memoir of War, Michael Duffy offers a different approach from the myriad memoirs on this horrible conflict. Serving as an executive officer in C battery in the 7th Battalion of the 9th Artillery at the tender age of 22, Duffy may not have seen the daily carnage suffered by those in other branches, but this did not mean the war had any less of an impact on the Chicago native. Duffy relates his involvement from the day he arrives in Cam Ranh Bay on the eve of the Tet Offensive. The same diligence and exactitude Duffy was known for in using mathematics and trigonometry and making sure the guns were pointed in the right direction is seen in the systematic way he tells his story – a story not filled page by page with the horrors of war, but rather, relaying what was often the case for many soldiers during each day: extreme heat, interminable bone-drenching rains, and little sleep.

Punctuated throughout the book are the stories he would relay to others, whether to his captain or his hosts in Australia during a brief period of R&R. These stories were always about some event or events that took place back home. At first blush, the often-lengthy stories might appear to detract from the narrative of his time in Vietnam. However, the presence of these stories could rather be seen as the graphic representation of Duffy’s (as, likely, most all soldiers) attempt to maintain a hold of something from home while being tossed into the cauldron of chaos and death that was the Vietnam War.

This proverbial lifeline to home would be crucial upon returning home. When the American soldiers returned home from World War II in 1945, they were greeted as heroes in the United States. Cities and towns across the country held parades to honor the returning veterans and recognize the sacrifices they had made. But the homecoming was very different for most Vietnam veterans. They came back to find the United States torn apart by debate over the Vietnam War. There were no victory parades or welcome-home rallies. Instead, most Vietnam veterans returned to a society that did not seem to care about them, or that seemed to view them with distrust and anger.

Many of the young men who fought in Vietnam had a great deal of difficulty readjusting to life in the United States. Some struggled to overcome physical injuries, emotional problems, or drug addictions from their time in Vietnam. Others had trouble feeling accepted by their friends and families.

Rather than being greeted with anger and hostility, however, most Vietnam veterans received very little reaction when they returned home. They mainly noticed that people seemed uncomfortable around them and did not appear interested in hearing about their wartime experiences.

In addition, many veterans went from the jungles of Vietnam to their hometowns so quickly that they did not have time to adjust. Unlike previous wars, when it usually took weeks for soldiers to be discharged and transported home, U.S. soldiers often returned from Vietnam within two days. Returning to the safety and comfort of home so quickly made it more difficult for them to make sense of the danger and misery they experienced in Vietnam.

Duffy relates his transitional difficulty in the same way he relates his entire experience in Vietnam. He is not preachy; the process is cathartic without descending into pathos. Memories refuse to disappear. Surges of anger and frustration are painfully slow to fade. Along with a loving family, Duffy was able to put many of the ghosts to rest through painting he began roughly ten years after leaving Vietnam. He continues to paint, though his “Vietnam period” lasted roughly eight years, with his last painting coming in 1986.

From Chicago to Vietnam is not meant to be converted to film. It is not a political treatise nor is it another piece on the horrors of war. It is a very readable and thought-provoking story of a young kid from Chicago forced to mature during perhaps the worst year of the worst war in American history.

[signoff predefined=”Sponsored Review Program” icon=”book”][/signoff]