To say that Weldon Kees is an obscure poet is an understatement – outside of the poetry world you won’t find anyone who’s heard of him, and even in poetry circles he is something of an obscurity. Yet he was a peer of Robert Lowell’s and right there in poetry circles connected to Hart Crane, and was even deep in poetry and art circles around San Francisco – yet the most fascinating thing about him is his disappearing in July 1955 – an apparent suicide off of the San Francisco bridge. His body was never found. And his work, like his life, has become largely unknown.

[alert variation=”alert-info”]Publisher: Johns Hopkins University Press

Formats: Hardcover, eBook, Kindle

Purchase: Amazon | IndieBound | iBooks[/alert]

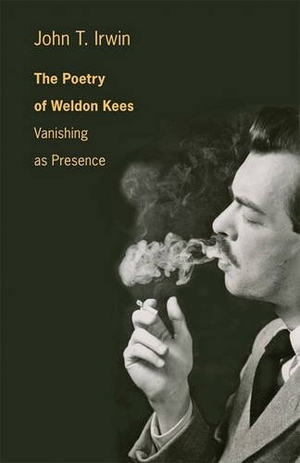

That’s where John T. Irwin’s short yet concise memoir comes in, detailing the final moments of Weldon Kees and some of the key poetry that makes him worth knowing. Little is known about Kees’s life itself. His childhood is completely absent and even a search reveals little to nothing. Who was Weldon Kees and what was his world? Even Irwin’s memoir gives little in the way of this – Irwin’s memoir details more specifically the time period from 1940 to 1955 where Kees was working for a magazine and as a book reviewer. This is the most prominent time in Kees’s life where he would write most of his poetry and create most of his art.

Until 1955 when police found his car abandoned near the Golden Gate Bridge and no sign of Kees anywhere. Two books were left at the bedside in his apartment after the disappearance. Dostoevsky and Unamuno. Much of Irwin’s memoir is spent digging for the meaning in this. They are two apt books, and an aesthetic final declaration for an obscure poet. Irwin’s goes into deep detail about these works and what they might have been saying as final statements from Kees himself.

But what was Kees saying by leaving these two pieces behind? The answers are complex and here Irwin’s book turns more into an extended essay life and the philosophy of suicide. Details of Kees’s life are scarce and left out in favor of the latter part of his life – little is known – but we do have his poetry which is a totality of spirit and poetic fervor. Irwin is right to highlight major pieces like “Statement With Rhymes” – one of Kees’s first major pieces. Irwin explains the influences of Hart Crane and Wallace Steve’s on Kees, poets who helped him form major pieces of poetry that would later make him famous in the poetry world.

But Irwin’s memoir is a nice little piece – almost more a lengthy essay which includes Kees’s art, and the writer’s life – it discusses the philosophy of Nietzsche and nihilism, Camus’ major influence on the idea of suicide and the bizarre and flat out strange nature of disappearances. Kees’s body was never found and he talked extensively of disappearing to Mexico leading many to believe he faked his own death – although to this day no work of Kees has turned up. For its brevity, it includes a lot and is a nice introduction into the world of Weldon Kees. But the excellence of Weldon Kees is what should be highlighted in this review. In a short and relatively unknown life, the work left behind speaks for itself and Irwin’s book is a celebration of that and poetry itself.

[signoff predefined=”Social Media Reminder” icon=”twitter”][/signoff]