Magical Realism manifests as extraordinary events beside the real: sometimes we call it magical realism, sometimes speculative, sometimes slipstream, and sometimes fabulist. A rose by any other name, right?

Whatever we call it, that innovative fiction is a fiction of doubleness, meaning that it is doubled in its approach to representing reality (the magical beside the real). Doubleness enables innovative fiction to navigate multiple relationships to multiple realities, but, pushed further, an expression of multiple realities is a particularly powerful tool for writers asserting the equality of multiple identities.

Doubleness can function most familiarly as parody. I can think of a fun, trenchant, example from a recent episode of SNL. In the clip linked below, Leslie Jones, Kenan Thompson, and Sasheer Zamata hang their premise on a mainstream scaffolding of Stranger Things (a very popular horror-sci-fi story about children caught up in a scientific experiment gone awry). Popular genres are often very likely to attend to traditional and problematic myths in mainstream popular culture because they’re marketed to that culture. The skit below holds a mirror to Stranger Things’ pop-genre form by asking why an African-American community is denied a presence.

SNL’s Stranger Things

The “doubleness” of innovative writing of any kind, but particularly within a popularly understood genre, becomes a potent site for conversation with and against mainstream popular culture’s assumptions. That’s because we can cast new thoughts onto a screen of former expectations and let them contrast. That contrast can result in perhaps the most common form of “doubleness”, as above: parody.

But “doubleness” in innovative fiction can also take on a non-parodic assertion of alternate realities and identities, as it does in Magical Realism.

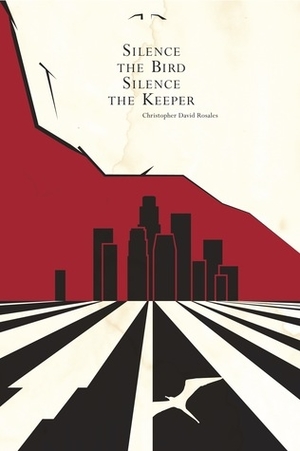

In the magical realist fiction I’ve written, like my first novel Silence the Bird, Silence the Keeper, the doubleness asserts the voices of marginalized discourse communities, let’s them tell their own story, because they don’t find traditional conventions adequate for expression.

That approach to magical realism’s doubleness comes down to a book’s representation of contradictions in realities. Magical AND Realism. Writing generally represents reality one of two ways. It either takes a realist stance (an attempt at sincere representation of a single reality), or a meta-fictional stance (a representation of multiple realities and self-awareness of the fiction’s construction). Magical Realism freely alternates between both stances toward representations of realities (the magical and the real, the marginalized and the mainstream, the transgressive within the traditional). And it doesn’t always have to manifest as “identity politics” to be about identity.

For instance, Italo Calvino’s If On a Winter’s Night a Traveler addresses the politics of the relationship between writer, character, and reader. It begins “You are about to begin reading Italo Calvino’s new novel, If on a winter’s night a traveler. Relax. Concentrate. Dispel every other thought. Let the world around you fade. Best to close the door; the TV is always on in the next room.”

Calvino challenges our relationship to reading through an allowance of multiple realities. No sooner has the world around the reader faded, than the author reminds the reader of the world around them (the TV is always on in the next room), which is at the same time the world of the text the reader is “about to read.” The prose represents one reality sincerely while at the same time reminding readers of their own judgments, assumptions, and expectations as a potentially separate and unique reality. Juxtaposition of both realities shows an acceptance of the fact of multiple realities, sure, but likewise multiple identities.

If we think about mainstream realist fiction as representing what could have happened, then Magical Realism is doubled: what could have happened co-exists with what was likely or unlikely to happen. That makes one use of Magical Realism a particularly useful narrative approach for the writer of a marginalized community. That writer’s identity is doubly linked to both a hope for what could happen and a knowledge of what mainstream society is likely, or unlikely, to allow.

Christopher David Rosales‘ first novel, Silence the Bird, Silence the Keeper (Mixer Publishing, 2015) won the McNamara Creative Arts Grant. Previously he won the Center of the American West’s award for fiction three years in a row. He is a PhD candidate at University of Denver and has taught university level creative writing for 10 years. Rosales’ second novel, Gods on the Lam releases in June, 2017 from Perpetual Motion Machine Publishing and Word is Bone, his third novel, is forthcoming 2018 from Broken River Books.

Christopher David Rosales‘ first novel, Silence the Bird, Silence the Keeper (Mixer Publishing, 2015) won the McNamara Creative Arts Grant. Previously he won the Center of the American West’s award for fiction three years in a row. He is a PhD candidate at University of Denver and has taught university level creative writing for 10 years. Rosales’ second novel, Gods on the Lam releases in June, 2017 from Perpetual Motion Machine Publishing and Word is Bone, his third novel, is forthcoming 2018 from Broken River Books.

[signoff predefined=”Editing Services” icon=”pencil”][/signoff]