Before writing The Girl Who Wrote in Silk I had little knowledge of, nor interest in, the Chinese immigrant and Chinese-American experiences in the Pacific Northwest. It took reading one paragraph in a book on the history of the San Juan Islands to change all that. That paragraph told of a smuggler who needed to dispose of the evidence of his smuggling when a revenue service cutter got too close to his boat. That “evidence” was Chinese people and his method of disposal was to bash them on their heads with a club and dump their bodies overboard. As one might imagine, I was horrified and had to learn more.

I soon learned the reason Chinese people had to be smuggled into the country at all was because of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 which was put into place by the U.S. government to severely limit the number of Chinese labor immigrants, though the wording made it difficult for any Chinese person to prove he wasn’t a laborer. This Act was the first immigration measure in U.S. history to discriminate against a specific ethnic group.

The Chinese people, especially those living in the Western states, were very well aware they were unwanted. Anti-Chinese sentiment was rampant. Towns and cities from as south as San Diego and as north as Vancouver, B.C. to as west as Wichita rounded up the Chinese people and drove them from their towns by force. All forms of violence was used by those trying to rid their communities of Chinese people: beating, stabbing, shooting, lynching, rape, arson… In Seattle the anti-Chinese mob forced the Chinese out of their homes and down to the dock where they were ordered to buy passage on a steamer bound for San Francisco. The territorial governor intervened and the Chinese were allowed to stay, but many chose to leave anyway.

What about Portland, you ask? Portland had its share of anti-Chinese sentiment. According to the Oregon Historical Society (www.ohs.org), in 1873 the Portland City Council passed a “500 cubic feet of air” ordinance that made it a crime to live in the cramped housing commonly inhabited by Portland’s Chinese. Thus, many Chinese residents were forced to leave the city. When a fire broke out in August of 1873, reportedly originating in a Chinese laundry, letters to The Oregonian placed the blame (or in this case, the credit?) on white people trying to drive the Chinese from the city. Throughout the 1870s and 1880s other attempts were made to forcibly remove Chinese people from neighborhoods such as Abina, Mount Tabor, and Guilds Lake. Most fled to downtown Portland or migrated to other parts of the state.

But it wasn’t all bad for Chinese in Portland. In fact, in 1880 Chinese made up 12% of the city’s population which was second only to San Francisco in all of the United States. Growth of the Chinese population kept up with the city as a whole.

Portland even welcomed in Chinese driven from other towns. On November 3, 1885, Tacoma forcibly drove out the entire population of its Chinatown and then burned every structure to the ground to prevent anyone from returning to their homes and businesses. Many of those driven out resettled in Portland. In 1906 Chinese men were driven from Humboldt County canneries. They, too, resettled in Portland.

The more I learned about this shameful time in our nation’s history, the more saddened and discouraged I felt. But stories like Portland’s gave me hope. By giving Chinese people a safe haven, Portlanders set the example for residents of other cities.

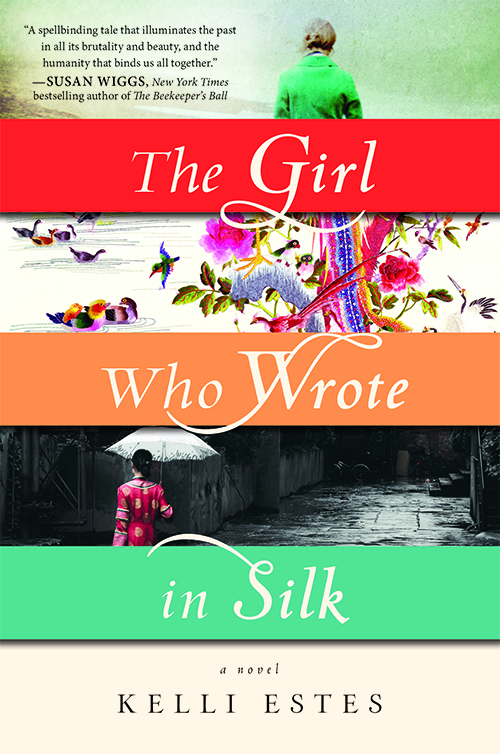

In The Girl Who Wrote in Silk a young Chinese-American girl is forcibly driven from her home in Seattle and becomes the lone survivor of a brutal event, the truth of which is never revealed to the public. This girl, Mei Lien, records the truth in the best way she knows how, through needle and thread. Her creation is discovered over a hundred years later by Inara, a white woman who researches the truth and discovers a connection to her own family that forces her to choose between keeping it a secret and dishonoring Mei Lien’s memory, or telling the truth and dishonoring her own family.

The Chinese experience in the 19th and early 20th centuries here in the U.S. is something that I believe all Americans should understand so we don’t repeat our mistakes. I hope The Girl Who Wrote in Silk helps achieve that in a small, yet entertaining, way.

Kelli Estes grew up in the apple country of Eastern Washington before attending Arizona State University where she learned she’d be happiest living near the water, so she moved to Seattle after graduation. Today she lives in a Seattle suburb with her husband and two sons. When not writing, Kelli loves volunteering at her kids’ schools, reading (of course!), traveling (or playing tourist in Seattle), dining out, exercising (because of all the dining), and learning about health and nutrition. Find her at www.kelliestes.com, or www.facebook.com/KelliEstesAuthor.

Kelli Estes grew up in the apple country of Eastern Washington before attending Arizona State University where she learned she’d be happiest living near the water, so she moved to Seattle after graduation. Today she lives in a Seattle suburb with her husband and two sons. When not writing, Kelli loves volunteering at her kids’ schools, reading (of course!), traveling (or playing tourist in Seattle), dining out, exercising (because of all the dining), and learning about health and nutrition. Find her at www.kelliestes.com, or www.facebook.com/KelliEstesAuthor.

[signoff predefined=”Social Media Reminder” icon=”twitter”][/signoff]